Patients need to get quality healthcare services whenever they need them.

Sometimes, however, a GP (General Practitioner) may not be able to fully assess and manage a patient’s health condition. In such cases, the referral feature allows healthcare providers to direct their patients to another specialist.

As a healthcare provider, you manage your patients’ health conditions and facilitate their referrals to other health professionals for better assessment and care. For instance, a cardiologist might refer a patient to a neurologist if the symptoms suggest a neurological issue.

This interdisciplinary approach ensures that patients receive the most appropriate and comprehensive care for their health needs.

Yes, specialists may refer patients to other specialists for specialized treatment, legal compliance, or patient-centric reasons (e.g., cultural preferences, clinical trials). Regulations like Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statute prohibit financially motivated referrals, ensuring decisions align with medical necessity. The receiving specialist invoices for their care, while the referrer bills for prior services.

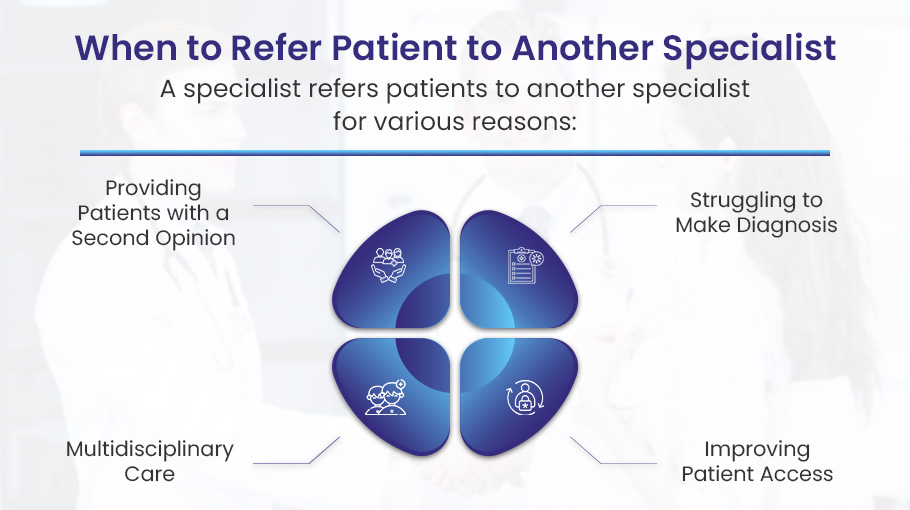

Why Does a Specialist Refer Patients to Another Specialist?

Referring a patient to another specialist is common, but it is not always necessary. A primary care physician or specialist may choose to refer patients for various reasons.

Therefore, to understand the best times to refer a patient to a fellow specialist, let’s discuss some reasons and scenarios below:

1). Lack of Procedural Expertise or Technology

When it comes to healthcare, specialists often refer patients to other specialists. This happens for a variety of reasons, but one common one is a lack of procedural expertise or technology.

For example, a general surgeon may encounter a patient with a complex pancreatic issue. While the general surgeon has broad training, they may lack specialized knowledge or skills related to complex pancreatic procedures.

In this case, the general surgeon would likely refer the patient to a hepatobiliary surgeon who specializes in surgeries related to the liver, pancreas and gallbladder. The hepatobiliary surgeon has received years of extra training and performed many more pancreatic procedures, putting them in a better position to provide optimal care for the patient.

The goal is to connect each patient with the most qualified specialist for their condition. This ensures patients receive the safest and most effective care.

2). Regulatory or Payer Requirements

Regulatory statutes like Stark Law exceptions and payer mandates often dictate when healthcare providers must refer patients elsewhere for certain treatments, tests or equipment. This system aims to provide appropriate, unbiased care while controlling costs.

For example, the Stark Law is a federal regulation that prohibits physicians from referring Medicare patients for designated health services to entities in which they have a financial interest. This law has exceptions that require referrals in certain situations.

One such exception is for Medicare patients needing durable medical equipment (DME) or advanced imaging services like MRI or CT scans. In these cases, the referring physician must send the patient to an approved, independent provider for those services.

As an illustration, let’s say a neurologist is treating a Medicare patient with symptoms of sleep apnea. The neurologist cannot perform the sleep study themselves if their practice has a financial stake in the sleep lab. Instead, they must refer the patient to an in-network, independent sleep clinic for the polysomnogram test.

This referral process ensures patients receive care from qualified providers without conflicts of interest influencing the referral decision. It helps maintain objectivity and prioritizes the patient’s best interests.

In addition…

Insurance payer rules like prior authorization requirements or in-network restrictions also drive many specialist referrals. If a procedure or service requires pre-approval or must be performed at specific in-network facilities, the referring doctor has no choice but to make that referral per the payer’s guidelines.

3). Patient Preference or Cultural Needs

When it comes to health care, it’s not just about skills and know-how. Patient needs and wants play a big role too. That’s why healthcare specialists may refer patients to other specialists at times.

One key reason is patient choice. Some want a specialist who gets their way of life and beliefs. Like, a female patient may feel more at ease with a female specialist for some check-ups. Or someone who speaks their tongue may be a better fit to make sure they grasp the whole health plan.

Language and cultural barriers can also lead to referrals. A cardiologist who only speaks English may refer a Spanish-speaking patient to a bilingual colleague. This allows the patient to communicate symptoms and understand treatment plans more easily.

At the end of the day, specialists just want their patients to get the best care possible. Sometimes that means looping in an expert who’s a better fit, culture-wise or just vibe-wise. It’s all about keeping the patient’s needs first.

4). High-Risk or Complex Comorbidities

Healthcare specialists also refer patients to other specialists when dealing with high-risk or complex comorbidities. Comorbidities mean having two or more medical conditions in one patient. Dealing with overlapping conditions can be tough for a single specialist. Therefore, it often needs help from different specialists who work together.

Sometimes, a patient’s primary condition is compounded by additional health issues. This makes their overall medical situation more complicated. In such cases, the primary care doctor or specialist may send the patient to another specialist for shared care.

For example, a diabetic patient with renal failure might be referred to a nephrologist (kidney specialist) to help manage the kidney-related complications alongside the primary care provider managing the diabetes.

Another common scenario is when a patient’s pre-existing condition poses a risk or requires special consideration during the treatment of a new condition. An oncologist treating a cancer patient with pre-existing heart disease may refer the patient to a cardio-oncologist. As the cancer patient goes through chemotherapy or radiation therapy, the cardio-oncologist’s job is to keep an eye on and take care of the patient’s heart health.

By involving specialists with expertise in specific areas, healthcare providers can ensure that patients receive comprehensive and coordinated care. This teamwork helps manage complex medical situations better.

5). Legal or Risk Management

Many patients are referred to specialists by their healthcare providers for legal or risk management reasons. This means that the provider wants to make sure they are giving the patient the best possible care and avoiding potential medical mistakes that could lead to a lawsuit.

Say a patient comes to their family physician with stomach pain. The doctor examines them but isn’t sure if it’s something routine like acid reflux or a more serious issue like appendicitis. To ensure the patient gets the right diagnosis and treatment, the family physician refers them to a gastroenterologist who focuses on digestive health.

The takeaway is that referring to specialists is often done to get patients the best quality care for their specific health needs. It also reduces the potential for errors that could lead to lawsuits and other legal issues. Doctors want what’s best for their patients while also making sure they don’t expose themselves to excess risk.

6). Emergent Complications

Healthcare specialists often refer their patients to other specialists for emergent complications that arise during treatment. This means that a patient’s condition suddenly and unexpectedly worsens while under the care of one doctor, requiring urgent attention from another specialist.

For example, a patient with stomach ulcers sees a gastroenterologist for treatment. But during the course of care, one of the ulcers perforates or ruptures, creating a life-threatening emergency. The gastroenterologist immediately refers the patient to a trauma surgeon who can operate right away to repair the perforation.

Referrals for emergent complications allow doctors to get their patients the specific, timely care they need when an unexpected crisis occurs. The gastroenterologist provides ongoing management of the ulcers, while the trauma surgeon has specialized skills to resolve the perforation. Coordinating care between specialties in this way can be lifesaving.

The same is true across healthcare. A psychiatrist treating a suicidal patient may need to urgently involve an endocrinologist and psychiatric hospital if a thyroid storm suddenly develops.

In this way, emergent complications often require a team of specialists with focused expertise to provide the best patient care and prevent catastrophic outcomes. Referrals allow doctors to rapidly deploy the right specialist for the situation at hand.

7). Participation in Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are research studies that test new treatments or drugs to see if they are safe and effective. They are an important way for doctors to gain more knowledge and provide patients access to cutting-edge therapies.

For example, a dermatologist treating a patient with severe psoriasis may refer them to an oncologist running a clinical trial of a new biologic medication. The oncologist is testing whether this new drug can clear up stubborn plaques better than existing treatments. By enrolling in the study, the patient gains a chance to try this promising new option. They also get carefully monitored care from the expert trial doctors. And they are helping advance medical research that could benefit many future patients.

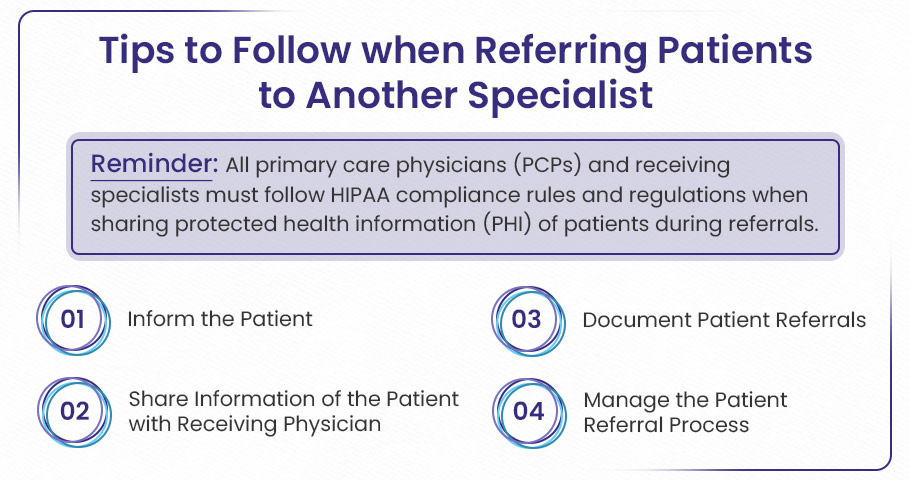

How to Refer a Patient to Another Specialist?

Referring a patient takes coordination, but is manageable if you break it down. This quick how-to guide will walk you through making a seamless referral:

1️⃣

Document Medical Necessity & Obtain Informed Consent

➜ Document the Reason for Referral: Include details like the clinical findings, test results, and any treatments that didn’t work. This is important for legal and insurance purposes.

➜ Explain the Referral to the Patient: Clearly discuss why the referral is needed, the risks, benefits, and any alternatives.

➜ Obtain Verbal Consent: Get the patient’s agreement after explaining the referral, and make a note of it (e.g., “Patient agreed after explanation”).

➜ Provide Written Summary: Send a written summary of the referral and the discussion to the patient through a portal or email to ensure they understand.

2️⃣

Coordinate with the Receiving Specialist

➜ Contact the Specialist: Before sending the referral, make sure the specialist accepts the patient’s insurance, has room for new patients, and agrees with the medical reasoning for the referral.

➜ Use Secure Communication: Use a HIPAA-compliant system like EHR messaging to maintain patient confidentiality.

➜ Share Relevant Records: Send all necessary patient records electronically, including test results, imaging, and progress notes, to avoid repeating tests.

3️⃣

Prioritize Urgency & Define Responsibilities

➜ Categorize Referrals by Urgency:

- Emergent: Schedule immediately for life-threatening conditions (e.g., unstable angina).

- Urgent: Schedule within 72 hours for serious conditions (e.g., new cancer diagnosis).

- Routine: Schedule within 14–30 days for stable conditions (e.g., osteoarthritis).

➜ Define Responsibilities: Clarify, in writing, who is responsible for the patient’s care during the referral process, including tasks like prescribing medications and monitoring symptoms.

4️⃣

Streamline Appointment Scheduling

➜ Train Staff for Scheduling: Ensure your team is trained to help patients book appointments while still in the office, especially for urgent referrals.

➜ Provide Appointment Details: Give the patient all the necessary details, including the specialist’s contact info, office location, and insurance pre-authorization info (if needed).

➜ Track Follow-Up: Use EHR tools to set reminders for follow-ups and ensure appointments are not missed or overdue.

5️⃣

Use Standardized Referral Agreements

➜ Create Referral Agreements: Set up agreements with specialists that include:

- Timeline: When the initial consultation and report should happen (e.g., consult within 7 days, report within 48 hours).

- Communication Protocol: A clear way to contact specialists for urgent updates (e.g., direct phone line).

- Billing Responsibilities: Avoid duplicate charges for shared tests.

6️⃣

Monitor Specialist Performance

➜ Track Specialist Performance: Monitor the timeliness of consultation reports and patient outcomes through your system (EHR).

➜ Address Delays: If the specialist misses deadlines:

- Discuss Privately: Start by addressing the issue directly with the specialist to understand any workflow barriers.

- Escalate If Needed: If the problem continues, consider escalating it to a peer review committee or ending the referral relationship.

7️⃣

Navigate Insurance Barriers

➜ Out-of-Network Referrals: If an out-of-network specialist is necessary:

- Submit a Letter of Medical Necessity to the insurance company to explain why the referral is important.

- Use State Laws: Cite relevant state laws (e.g., New York’s Emergency Surprise Bill Law) that support out-of-network referrals.

8️⃣

Document Patient Refusals

➜ Document the Refusal: If a patient declines a referral, make a note of the reason (e.g., transportation issues).

➜ Offer Alternatives: Suggest other options, like telehealth consultations, to meet the patient’s needs.

➜ Reassess at Follow-Up: During follow-up visits, check if the patient’s concerns have been addressed, and reassess the situation as necessary.

Patients have the choice of whether or not to see a specialist if their physician recommends it. Should they decide not to go, the doctor will inquire as to why at their next appointment and document the reason. This concludes the referral process, however providers can still urge patients to reconsider seeing specialists later on if they have a change of heart.

Key Regulations Governing Referrals

Healthcare specialists in the United States often need to refer patients to other specialists for optimal care. However, there are important legal considerations around these referrals that specialists should understand.

📢 Stark Law (Physician Self-Referral Law)

The Stark Law has a section called the Physician Self-Referral Law. This law generally prohibits doctors from referring patients to other healthcare providers for certain “designated health services” if the doctor has a financial relationship with that provider.

For example, if a cardiologist has an ownership stake in a diagnostic imaging center, they cannot refer patients to that imaging center for MRIs, CT scans, etc.

Specialist-to-Specialist Referrals: When are they allowed?

While the Stark Law aims to prevent improper financial relationships from influencing referrals, it does not prohibit all specialist-to-specialist referrals. In fact, these referrals are permitted as long as there is no improper financial incentive involved.

For example, if a cardiologist refers a patient to an orthopedic surgeon for a knee replacement, this referral would be allowed under the Stark Law, provided that the cardiologist does not have an ownership interest in the orthopedic surgeon’s practice or receive any financial compensation for the referral.

Exceptions to the Stark Law

The Stark Law provides several exceptions that allow physicians to refer patients for DHS, even when a financial relationship exists. Some of these exceptions include:

✅️ Referrals within the same group practice: If both the referring physician and the specialist are part of the same group practice, the referral is permitted.

✅️ Medically necessary services: Referrals for services that are deemed medically necessary for the patient’s treatment are allowed, even if a financial relationship exists.

✅️ Certain compensation arrangements: The Stark Law provides exceptions for specific compensation arrangements, such as bona fide employment relationships or personal service arrangements, as long as they meet certain requirements.

The key is that specialists can freely refer patients to other specialists, as long as the referring provider does not stand to improperly profit off that referral.

📢 Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

The AKS makes it illegal for healthcare providers to receive any sort of compensation, whether financial or otherwise, in exchange for patient referrals. This includes referrals between specialists.

For example, it would violate the AKS if:

❌ Specialist A refers patients to Specialist B in exchange for a percentage of Specialist B’s revenue from those patients.

❌ Specialist A refers patients to Specialist B in exchange for Specialist B referring patients back to Specialist A. This is considered a reciprocal relationship.

❌ Specialist A receives any other sort of compensation, like gifts, from Specialist B in exchange for referrals.

The main goal of the AKS is to prevent medical decision-making from being improperly influenced by financial incentives. Patient care and referrals should be based on patient needs, not quid pro quo relationships between providers.

Permitted Referrals Under the AKS

The AKS does NOT prohibit referrals between specialists when:

✅️ The referral is based on the patient’s medical needs. For example, referring a patient to an orthopedic surgeon for a broken bone.

✅️ There is no exchange of compensation or promises tied to the volume of referrals between the specialists.

✅️ The compensation received is fair market value for professional services, not for the referral itself. For example, receiving compensation for covering another specialist’s patients is okay.

The key is that referral decisions are made for the right reasons − what’s best for the patient. As long as we are making referrals based solely on patient needs, without compensation connected to the referral itself, we are in compliance with the AKS.

📢 Ethical Guidelines (AMA)

The American Medical Association’s Code of Medical Ethics offers clear guidance on referrals. It states that referrals should be based on the patient’s needs, not the physician’s financial interests. As specialists, we have a duty to recommend the most appropriate doctor for our patient’s condition, not the one who provides us the greatest financial incentive.

For example, if I am a cardiologist treating a patient who could benefit from seeing a gastroenterologist for an issue unrelated to their heart, I should refer them to the GI doctor best suited to treat their condition. I should not refer them to a GI doc just because he and I share ownership in an ambulatory surgery center. That would constitute self-referral and violate ethical principles.

The key is to think, “What physician would I send a family member to for this issue?” That should guide your referral choice. Always act in the patient’s best medical interest, not your own financial interest. Document your rationale for referrals to show you considered quality of care.

Making referrals based on financial gain erodes patient trust and violates our ethical responsibility as physicians. But when we refer with integrity, we uphold our duty to put patients first.

Who Receives Reimbursement? Referring Specialist or Receiving Specialist?

When a specialist refers a patient to another specialist for care, who gets paid for what? This is an important issue for specialists to understand.

🅰️ The Receiving Specialist Bills for Their Services

The specialist who directly treats the patient can bill for the care they provide. This includes things like:

- Consultations

- Procedures

- Tests

- Follow-up care

So if a cardiologist refers a patient to a surgeon for bypass surgery, the surgeon can bill for performing the surgery.

🅱️ The Referring Specialist Bills Only for Their Own Services

The referring specialist can only bill for the services they personally delivered prior to the referral. For example, they could bill for:

- The initial patient evaluation

- Diagnostic tests they performed

- Office visits prior to the referral

In the surgery example, the referring cardiologist could bill for the initial consult and tests leading to the referral. But not the surgery itself.

Examples to Make it Clear

Cardiology to Heart Surgery

- Cardiologist refers patient to cardiac surgeon for bypass surgery

- Surgeon bills for the bypass surgery

- Cardiologist bills for evaluating the patient initially

Oncology to Radiation Oncology

- Oncologist refers patient to radiation oncologist

- Radiation oncologist bills for providing radiation therapy

- Oncologist bills for initial cancer evaluation and treatment planning

References: